Christmas castaway

More than 80 years before the movie in a similar vein was released, Guernsey's own castaway was stranded on the Humps - and had a far more unfortunate fate than actor Tom Hanks' fictional character...

AS CASTAWAY stories go, Guernsey's tale from the silent movie days had perhaps too tragic an end to merit changing the screenplay that convinced Hollywood star Tom Hanks to take up the role.

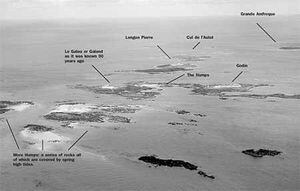

For a start, the Humps north of Herm in the darkest depths of winter are a lot less appealing than whichever sun-blessed, uninhabited Fijian isle Hanks was afforded in the 2000 movie, Cast Away.

Hanks escaped – which is more than can be said of poor Harry Manning, whose demise was told fully and impressively several years ago in this paper by Stephen Furniss.

But, for the first time, LOOKback is able to unveil prints of the grim search for Manning, who lost his life weeks after the ketch, Iris, went down off Fort Le Marchant in a fierce gale a week before Christmas, 1918.

They are the property of Peter Brehaut, who contacted LOOKback to offer them as the basis of a return to this tragic story of a poor man who should not really have been aboard the Iris and was presumed, when found, to be his brother.

Discovered on 23 January, more than six weeks after the ketch went down, the body was initially thought to be Irishman Robert Manning due to the fact that he was discovered in a waterproof coat which bore the name, R. F. Manning, which was also scratched onto his belt.

But it was a borrowed coat.

Harry Manning – real name Henry George – had not been an active seaman for years and had only just arrived in Fowey with his wife and children when he answered the call to stand in on the Iris.

Proof that it was Harry and not Robert came when the former's wife, Emily, saw the Guernsey newspaper report, which detailed the tombstone tattooed on his chest, as well as other markings.

She is said to have shouted, 'My Harry, my Harry', before collapsing on the floor.

The poor woman was to be put through more distress when the body arrived back in Fowey, officially named as Robert Manning. She had the awful task of identifying the remains and swearing on the Bible that it was, in fact, her husband Harry.

While another shipmate, Jack Collins, was soon washed ashore drowned in Fontenelle Bay, it seems Manning had escaped the sinking Iris with the skipper, Captain Rickard.

Had they stayed put, the pair in all likelihood would have been saved. After all, it was so close to land that a decent picture of the ill-fated and redesigned yacht with a draught of 13ft was taken and used on the front page of the next day's Guernsey Evening Press.

But, spooked by the situation, they jumped into a dinghy and were swept across the Russel to the rocks that become islands north of Herm on spring tides.

Le Galand is where their dinghy hit land and, it would seem, all too forcefully to be used again, as part of a boat was found on the Garindes rock near Galand and more of it was used as part of the Christmas castaways' rocky shelter.

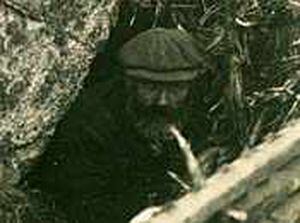

When the discovery of Manning's body was made, it was all too shocking.

While islanders had tucked into festive fayre, he'd had nothing more than limpets to survive on.

Clues in the form of abandoned socks suggest that at some point in the perishing ordeal, Capt. Rickard had plumped to try his luck at swimming to Herm, only to find the currents, cold and distance a fatal combination.

Manning stopped, waited and died at Le Galand, his body found 40ft away from the shelter, ingeniously made against a rocky ledge with turf, seaweed, marsh mallow plants and sticks, as well as part of the boat.

In front of the shelter, the ground was broken up and the brushwood growth was cut off the stalk cleanly, as it could be done with a penknife.

The stalks of the shelter were bound together with spun yarn and around were hundreds of empty limpet shells.

Inside the shelter were two quality socks and another was found nearby on a rock, tied at one end with a strip of handkerchief border and his attempt at signalling passing boats.

Ninety years on, Captain Barry Paint, who knows the rocks so well, said he is not surprised that Manning's attempt at attracting attention failed.

'The only attention he might have called on would have been fishermen, because the ships going up and down the Russel would not be looking in that direction but looking at the transits taking them up or down the Russel,' he said on hearing the tale.

The esteemed modern-day pilot can easily visualise how Manning and Capt. Rickard ended up at Le Galand, nowadays referred to as Galeu.

'If they were in a small boat, it looks as if the wind would have been from the south-west or west and the tidal currents would have been running to the north-east.'

Although there was no firm proof of a boat transporting them all the way to Galeu, it is very likely that it did.

Capt. Paint explained that swimming such a distance would have taken a long while and in the depths of winter it is unreasonable to expect someone to survive the cold.

'With a strong north-west or westerly wind and if the ship went down around low water, it would be possible for someone to swim from Fontenelle bay to the Galeu.

'He would have been carried by the current for about two-and-a-half hours toward Herm (south-easterly through the Doyle passage then southerly in the Little Russel). After half-tide up he would then be carried to the north-east. The distance he would have to swim is difficult to work out because I don't know if it was a neap or spring tide.

'The distance is about three-and-a-half miles as the crow flies, so it would take three to four hours, allowing for the rough drift of tide.'