One girl’s war

The title of Nancy Allen’s book, One in a Thousand, refers to the fact that she was one of the 1,000 children left in Guernsey after the evacuation. Taken from reminiscences with her father and snippets and press cuttings from his wartime diaries, it was originally published in 1995. Now revised, One in a Thousand has been republished by Nicholas Drake and The Monnaie Fellowship Trust LBG. Shaun Shackleton reports...

NANCY MAY ALLEN was seven years old when she heard the news that mail boats were being sent to her island home to evacuate people to the mainland.

‘I was at the Ker Maria Roman Catholic Infants School, which is opposite where M&S is now, on Route Carre,’ explained Nancy. ‘School children were the first to be evacuated, starting on 21 June 1940.’

As the nuns from her school were preparing their pupils for evacuation, Nancy thought she saw one of them sew a crucifix onto a boy’s skin. She ran home, terrified.

‘I didn’t know it at the time but she was sewing it to his vest,’ said Nancy. ‘But it convinced my mum and dad that we should all stay together in Guernsey.’

Less than an hour after Nancy had run home, the last ship, The Viking, left the harbour.

Nancy said that life got back to being as normal as possible quite quickly. Then, on the evening of Friday 28 June 1940, after returning from the beach, their greatest fear became real.

‘Within an hour of us being back home, the dreaded grey planes, with their huge black crosses, were swooping down on our pretty, unspoilt, peaceful island. The beach which we had just vacated was being machine gunned. The sheds at the Castle Emplacement which my dad had been visiting were blown up. The worst hit was the White Rock harbour.

‘We lost many brave men that day, they just had nowhere to run, diving under their lorries which were catching fire and exploding.’

On that day, 22 people were killed and 33 seriously wounded. Two days later, the Germans landed on Guernsey. Within a couple of months soldiers began patrolling the streets, checking for lights on after curfew. Nancy was so scared that they were going to take her mum and dad away that she’d creep into their bed at night.

‘Strange that when daylight came I was never really frightened of the Germans,’ she said.

Early on in the Occupation, despite the curfew, islanders still found ways to enjoy themselves.

‘Next to my dad’s barn was Grove House, a Guernsey granite building with very large rooms. In the early evening, my school friends and I would sit on the windowsill and watch the dancers enjoying themselves.

‘My family and I were invited to join in during the first week of Occupation and I can remember being put on the table to sing, ‘We’re Going to Hang out the Washing on the Siegfried Line’. My dad had bought a set of drums that week from Fuzzey’s in Town and our next door neighbour was an expert on the piano. Everyone sang at the top of their voices and finished with our own anthem, Sarnia Cherie.’

As her mum suffered badly from depression, Nancy would spend a lot of time with her dad, Bill.

He had a rotavator and was allowed a small Morris van and a small amount of petrol a week and tilled greenhouses and outside land for the States Essential Commodities Committee, growing potatoes and vegetables to sell to the public by controlled rationing.

‘I would go along with him at weekends and sit on the front of the large rotavator as he went up and down the fields. I carried a tomato basket and would be jumping on and off as soon as I spotted the old potatoes that dad had unearthed while tilling the ground. We came home at the end of the day covered with dirt and I would be very lucky if I had found six or seven old potatoes.’

As rationing became harsher, other, more unusual, foodstuffs had to be tried.

‘We were also given a seaweed called carrageen moss which mum boiled down and the juice was used as a form of jelly. If you were lucky to have any flavouring left from pre-war times, it came in very handy to flavour it.’

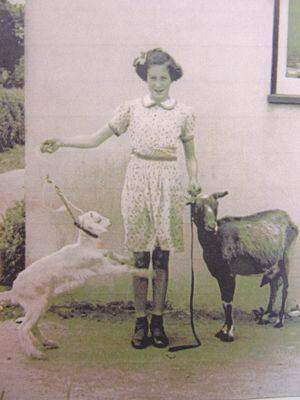

The family kept goats and also rabbits and chickens in hutches, which they’d bring in at night to save from being stolen after curfew. A hugely resourceful and inventive man, Bill not only cured the goat skins and rabbit pelts, he grew his own tobacco, devised a tobacco press and a hand-operated cutter, dried seawater for salt, fashioned bicycle tyres from hose pipes, built a haybox (an early slow cooker), and made a crystal set. Nancy used to listen to the BBC on it at Bill’s barn through earphones.

It was near here, however, that Nancy witnessed what no child ever should.

‘The old granite barn stood alongside the recently constructed German railway, close to the level crossing with Route Militaire. I saw my dad walking along the road towards the railway crossing so I decided to run along and join him. Down the road came a lorry carrying long steel rail tracks. The lunch-time train taking the prison labourers back to the barracks was coming down the track. The lorry was travelling at speed, the driver not hearing the quiet train whistle as it approached the road crossing. The oncoming lorry smashed into the packed trucks, derailing and overturning them, then sending the long rail lines and girders into the startled men. The screams of injured and dying men were chilling, their crushed and bleeding bodies were strewn all over the road. The OTs riding in the engine jumped out and just threw the dying and dead into my dad’s field alongside the track.’

As the Occupation wore on, locals rejoiced every time a Red Cross parcel arrived. Then, on 27 December, 1944, the Red Cross ship the SS Vega arrived with 750 tons of food and medical supplies.

‘The wonderful taste of chocolate (I had completely forgotten the taste), tinned meats, cereals and a special gruel which mum made up like a custard.’

Then, several months later, came the day that Nancy would never forget – 9 May 1945.

‘The British troops landed. My mum never got around to cooking that day. My dad, after so many attempts to shave, with me running outside, jumping on and off our garden wall shouting out every five minutes, “Dad just come out quick and see these planes, they are not the black German ones, they are British. Look”.’

But that was not the end of Nancy’s adventures.

On 18 May 1946, her parents received a letter from the States of Guernsey Education Council. Nancy had been chosen as one of 20 children going to London to see the Victory Celebrations. £108 had been raised through the Guernsey Evening Press by the then editor Bill Taylor.

‘It was two children from each school,’ explained Nancy. ‘I wasn’t supposed to go but the girl chosen had flat feet. I went with Frank Corbett from Vale School. Reporter Dorothy Dowding from the Press came too. It was wonderful.’

It sounds it, too. During their week in London they visited Westminster Abbey, 10, Downing Street, Fleet Street, the Tower of London, St Paul’s Cathedral, Eaton College, Windsor Castle, London Zoo, HMS Discovery and the Victoria Memorial to watch the parades and processions of the Victory Celebrations.

‘We were looking straight ahead to Buckingham Palace and had a clear view of the King and Queen leaving in their state carriage. The Queen looked lovely in lilac and the King in admiral’s uniform. Princess Elizabeth was in blue with matching hat and Princess Margaret in turquoise with a white hat. It poured with rain at 1 o’clock, but even that did not dampen out spirits. At 3pm, our party was able to leave and walk with many thousands of people all singing and waving flags.’

For children who had probably never left the island before, it was literally travelling to another world.

‘What a trip it was,’ said Nancy. ‘When we were on the boat we were all terribly sick. But we soon forgot all of that. It is something that has stuck in my mind all the time.’

A special memory of the trip is kept for a newsagents opposite the children’s hotel that sold ice cream.

‘After five years of German rule, short of food and never seeing an ice cream for all that time, they were delicious. The shopkeeper couldn’t believe his eyes, there were 20 of us children, every morning at 6 o’clock, in a queue when he opened his shop, all asking for ice creams before breakfast.’

From leaping off a rotavator to save stray spuds and eating boiled-down seaweed to watching a royal procession and devouring ice cream for breakfast, Nancy’s memories are an essential insight into how a child experiences the sadness, hardship, happiness and wonder of living through a war and, ultimately, a touching tribute to the parental, particularly paternal, love that got her through.

One in a Thousand by Nancy May Allen is £6 and available from the porch of the Monnaie Chapel of Christ the Healer, Perry’s Guide reference: 23H2 or from director Nicholas Drake on 267071. Nancy, together with her husband Len, has been a member of the congregation for 30 years and all proceeds from the book will go to the Monnaie Chapel.

For further information on the chapel, visit www.monnaiechapel.co.uk.