How the internet as we know it came to be, thanks to subsea cables

Despite talk of the ‘cloud’, the vast majority of connectivity is deep under the ocean.

Deep beneath the sea lays a vast network of hidden cables handling the majority of the globe’s internet activity.

These cables carry 99% of the world’s data, and in the age of social distancing, their role is more important than ever in keeping people connected.

As Google announced plans to install a new cable between the US, the UK and Spain, we dive into how global communication is handled, how it came to be and how it works.

– Where did it all start?

The Victorians are considered pioneers in submarine connectivity, having set a world first in 1850 with a telegraph cable across the English Channel between the UK and France.

By 1858, the first transatlantic submarine cable was laid between Ireland and Newfoundland, Canada.

However, Victoria’s 99-word message is said to have taken 17 hours and 40 minutes to reach the president, and the cable failed within a few weeks.

Nevertheless, it paved the way for the levels of connectivity we use on a daily basis today.

Since 1986, submarine telecommunication cables have been made using fibre optics.

Some of the old huts where early cables were housed can still be found dotted around the UK, such as one on Aberbach beach in Pembrokeshire, Wales, which has been converted into a holiday home.

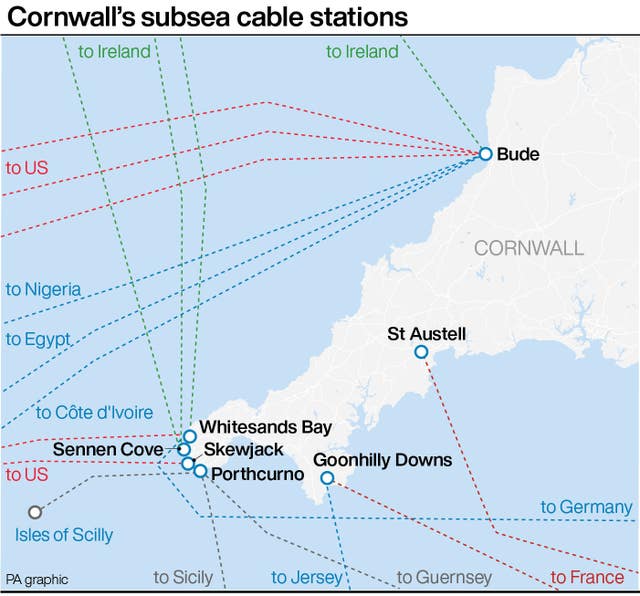

– How many of these cables feed into the UK?

There are hundreds of cables driving connectivity under the sea.

Many from the US come into Cornwall and Ireland, while south east and eastern regions of England are plugged into mainland European neighbours.

Scotland is largely hooked up to Nordic countries, as well as its own smaller isles.

– How are the cables laid?

Cables are installed up to 8,000 metres below sea level.

Careful planning is needed to map the ocean bed, to reduce the environmental impact.

They can then be connected to data centres on either side.

– What if there is damage?

Undersea cables are damaged all the time by various incidents.

Seismic activity is one example – a 2006 earthquake in Taiwan damaged eight undersea cables, cutting off communication to Hong Kong, south-east Asia and most of China, but this type of damage is not a concern for the UK where serious earthquakes are unlikely.

Impact from commercial fishing trawlers or ships’ anchors are more likely in UK waters.

Fortunately, cable owners support each other if a neighbouring cable is damaged, meaning we never really notice a disruption to service.

Repair ships are deployed to scoop up damaged cables, fix the issue on board, and put the cable back under the ocean.

– Why not use satellites?

Underwater cables can transmit a lot more data than satellites and are cheaper to operate.

– Who owns them?

Many big private companies and groups now operate their own cables, largely to support their service needs.

Google is the latest to announce plans of a new cable running between the US, the UK and Spain, which will help it maintain things like video communication platform Meets and Gmail.

Other tech giants are in on the act, including Microsoft, Facebook and Amazon.