Atlantic Ocean current could collapse much sooner than thought, study suggests

The climate system that keeps the northern hemisphere mild and wet could collapse this century, it said, though the results are far from certain.

An Atlantic Ocean current that brings warmth north from the tropics could collapse much sooner than scientists have previously thought, a new study suggests.

Known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), this current prevents the UK and other countries in north-west Europe from having the same icy winters often experienced at the same latitudes in Canada.

As the warm water flows north it cools and evaporates, becoming saltier and denser, which makes it sink and head southwards before it is pulled to the surface and warmed again, repeating the cycle.

Greenhouse gases produced by people since the industrial revolution have been warming the ocean and melting ice in the polar regions, changing the temperature and the amount of freshwater in the Atlantic.

Many climate models show the Amoc is likely to weaken in future because of global warming and the Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change has suggested it could lead to a collapse in the 22nd century.

Another effect would be to increase the temperature of the tropics even faster than is happening currently as heat that would normally be brought north would remain there.

The new study, published in Nature Communications, suggests a full or partial collapse is “most likely” to occur between 2025-2095, describing a general weakening of the current as it approaches a tipping point.

Professor Peter Ditlevsen of the University of Copenhagen and lead author of the study said he was “pretty alarmed” by the results but that there is still a wide degree of uncertainty of when a collapse would occur and how fast its consequences would take hold.

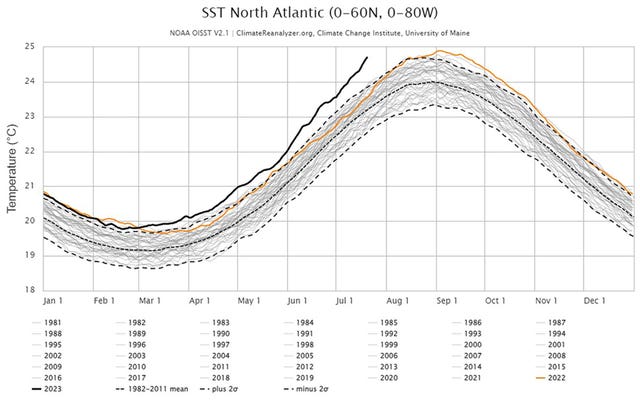

Other scientists have questioned the accuracy of the findings, saying the study’s reliance on using sea surface temperature data as an indirect measure of changes to the Atlantic current over the previous 70 years is not a reliable method for modelling the future.

Oceanographers have been directly measuring the AMOC only since 2004 and many of them say it is too soon to be able to confidently identify a long term trend.

These suggest that when the AMOC did collapse, it caused the average temperature around the North Atlantic to plummet by as much as 15C within a decade.

Asked if human-produced greenhouse gases were weakening the AMOC, Prof Ditlevsen said: “It is very unlikely that we’d see changes not seen for 12,000 years just by chance.

“We’re pretty sure that the perturbation we are doing with the emissions of greenhouse gasses is the single most important cause.”

Professor Penny Holliday, head of marine physics and ocean circulation at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, described the AMOC’s collapse as a “high impact, low likelihood scenario” and that decades worth of observations would be needed to identify a tipping point.

“Energy supply and demand would change rapidly with new climate conditions and infrastructures would need heavy investment to adapt and cope.

“The patterns of vector-borne disease and health (including mental health) would be profoundly affected.

“Worldwide, many land and marine ecosystems would be unable to cope and adapt to such fast changing climate conditions and biodiversity would be severely impacted.”

She said of the study: “They describe the potential for Amoc collapse within a few years as ‘worrisome’ and the evidence as something that we should not ignore.

“It’s hard to disagree with that.”