What does the surprise rise in unemployment and robust wage growth mean for me?

The latest official figures are being watched closely ahead of the Bank of England’s June 20 interest rate decision.

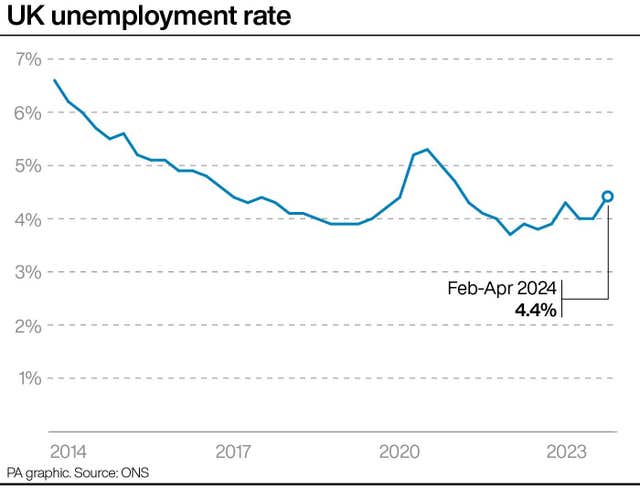

Britain’s jobless rate has reached its highest level for two-and-a-half years, suggesting the cracks in the employment market are widening.

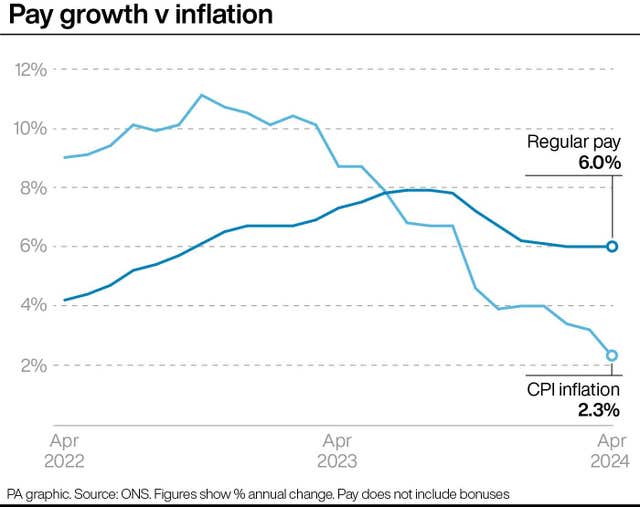

In better news for cash-strapped households, wages continued to outstrip inflation at the fastest pace since the three months to August 2021, according to the latest data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

The figures are being watched closely ahead of the Bank of England’s June 20 interest rate decision and what it might mean for the prospects of a cut.

Here we take a look at what the latest figures mean and why they are so important:

– Why has the unemployment rate gone up?

The rate of UK employment lifted unexpectedly to 4.4% in the three months to April, up from 4.3% in the three months to March and the highest level since July to September 2021.

Experts believe this reflects the impact of interest rates remaining at their highest since 2008, at 5.25%, with many firms delaying hiring decisions.

The ONS data also showed vacancies dropping sharply once again, down 12,000 to 904,000 in the three months to May, while the number of UK workers on payrolls is estimated to have fallen once again, down 3,000 to 30.3 million in May.

The figures showed regular earnings growth remained unchanged at 6% in the three months to April and continued to outstrip price rises – up 2.9% when taking Consumer Prices Index (CPI) inflation into account.

This is the highest level of real wage growth since the three months to August 2021.

Wages were sent climbing higher as the cost-of-living crisis struck in the aftermath of the Covid pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which sent energy costs soaring and saw employees demand higher salaries.

Earnings growth has been edging lower since reaching a peak last summer, but has remained at 6% for the past three data releases from the ONS.

UK earnings growth has also recently been boosted by the near-10% increase in the National Living Wage on April 1, when nearly three million people benefited from a rise from £10.42 an hour to £11.44 an hour, with many firms hiking workers’ pay ahead of this.

Rising wages means workers are better off, but high earnings growth also fuels inflation and is therefore seen as being unhelpful to the Bank of England in its battle to bring CPI inflation back to its 2% target.

The Bank is watching the jobs market, and wages in particular, closely as it looks to rein in CPI, and cooling earnings growth is seen as being key to paving the way for it to begin cutting interest rates.

A smaller-than-forecast drop in inflation in April, when it fell to 2.3%, is thought to have put paid to a rate cut at the Bank’s June 20 decision.

Many experts believe an August rate cut is still possible, but financial markets still see a November cut as being more likely.

Susannah Streeter, head of money and markets at Hargreaves Lansdown, said: “With the unemployment rate edging up, it means that actually employees won’t quite have so much bargaining power when it comes to demanding higher wages.

“However, wage growth is still pretty steamy, hovering around 6% for the February to April period.

“And that will niggle Bank of England policymakers who really want to see that relatively high rate of wage growth ease off because they’re concerned that companies may be forced to pass on those higher wage bills in the form of higher prices for goods and services.

“And that’s why it’s looking likely that they won’t cut interest rates in June. Of course, it’s bang smack in the middle of the election campaign as well.

“But still, an interest rate cut in August is possible.”

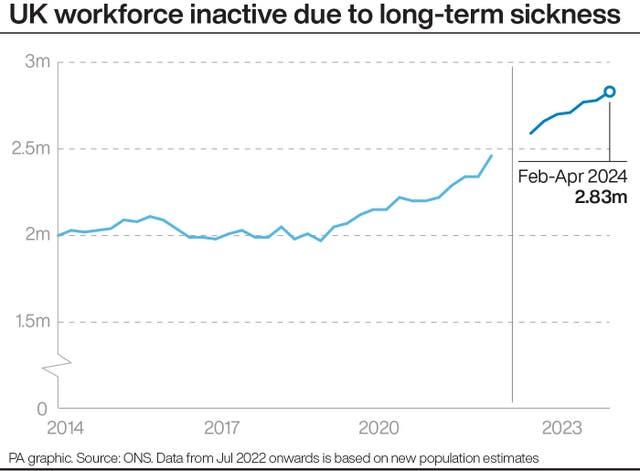

– Why is Britain’s inactivity rate so high?

The latest ONS figures also showed another increase in the number of people classed as economically inactive, with more than a fifth – 22.3% – of those aged between 16 and 64 not actively looking for work.

This has been pushed higher by record levels of long-term sickness – up again to an all-time high of 2.83 million in the latest set of figures.

This is also putting pressure on the employment rate – which fell to 74.3% in the three months to April, down from 74.5% in the previous three months.