UK: From pioneer of coal-fired electricity to harnessing the power of the wind

Key questions answered about the end of coal power in the UK.

With the closure of Ratcliffe-on-Soar, the UK has completed a journey from a pioneer of coal-fired electricity to leading the way among major economies in phasing out the fuel.

So here is a look at what has happened to the UK’s electricity mix and why.

From the opening of the world’s first coal-fired power station in 1882, the UK has been using the fossil fuel to provide electricity for 142 years, an era that is now at an end.

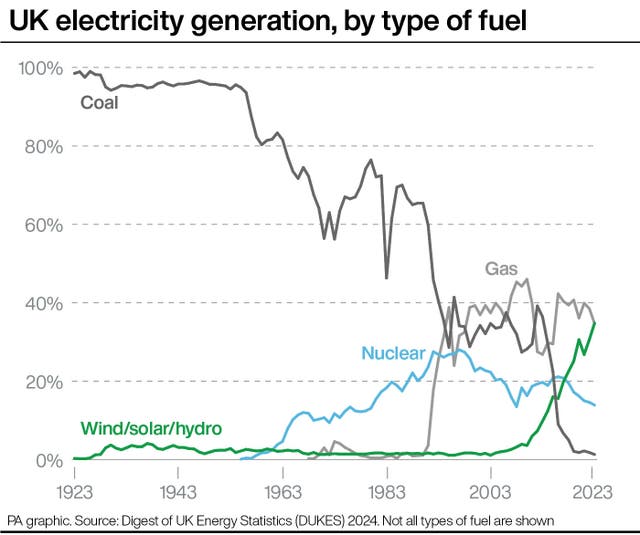

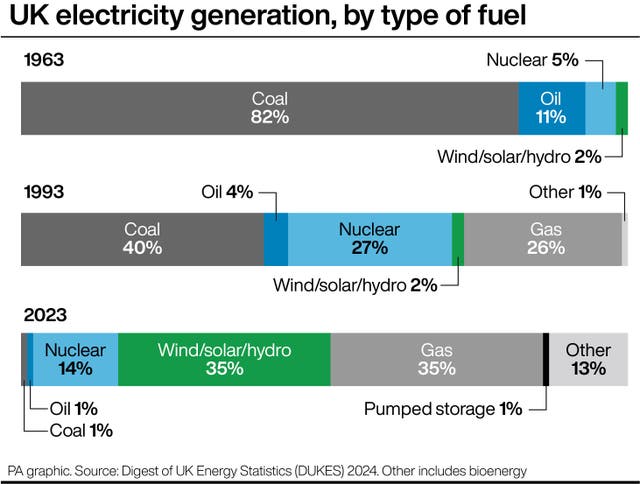

Coal provided the lion’s share of electricity in the UK until the 1990s, as the “dash for gas” using North Sea gas, saw cheaper and cleaner gas plants on the rise.

It dropped from nearly 40% of the UK electricity mix in 2012 to around 1%, with days at a time of the UK grid operating with no coal, in just over a decade.

Why did we phase it out?

While the dash for gas first saw coal pushed off the system, it was concerns about its climate role that led to dedicated efforts to phase it out.

In 2008, the UK passed the Climate Change Act to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050, a target which has since been increased 100% overall, known as “net zero”.

And by 2009, Ed Miliband, then energy secretary in Gordon Brown’s Labour government, had announced that only new coal plants with technology to capture and store their carbon emissions would be given the go-ahead, saying “this signals the era of unabated coal is coming to an end”.

As further measures in the 2010s targeted power sector pollution and drove the installation of more renewables, Conservative energy secretary Amber Rudd announced in 2015 that all polluting coal-fired power stations would be closed by 2025.

The 2025 closure date was brought forward in 2021 to October 2024, as the UK geared up to host the UN climate talks Cop26 in Glasgow.

By last year, the electricity mix in the UK had fundamentally transformed from what it had been just a few decades earlier.

In 2023, 47.3% of power came from renewables, with 28.7% from wind alone, with the rest from other sources such as solar, hydro, biomass, while 36.3% was from fossil fuels, mostly gas, at 34.3%.

Low carbon power, renewables and nuclear, accounted for 61.5% of the mix.

And in the second quarter of 2024, for when the latest data are available, more than half of the UK’s power came from renewables, some 51.6%, with 26.8% from wind – greater than the 25.4% share from gas, as coal dwindled away.

In addition to the power the UK generates domestically, there are undersea interconnectors allowing imports from sources such as French nuclear power and Norwegian hydropower.

Labour has pledged “clean power by 2030” which is expected to involve largely low carbon sources such as renewables but with some gas on the system to provide back up.

So the Government is looking to double onshore wind, triple solar power, and quadruple offshore wind by 2030, and there are also nuclear plants in construction or planned, but new nuclear capacity has faced delays, controversy and cost overruns.

But after years of falling electricity demand thanks to greater energy efficiency – and more recently high costs – the UK faces a further challenge of meeting rising power requirements as vehicles, home heating and industry switch to electricity to cut their emissions in the drive to reach net zero.

Ending coal use for electricity has helped the UK halve its greenhouse gas emissions since 1990, and has set a global precedent that major economies can phase out the use of the most polluting fossil fuel.

That is crucial for curbing climate change when use of the fossil fuel globally for electricity still rose 1.1% last year, according to energy analysis company Ember.

Clean energy is also cheaper, analysis shows, and shifting away from fossil fuels leaves the UK less reliant on price spikes in global energy markets.

But there are concerns about security of supply with a reliance on renewables that are intermittent, so the future grid will require a greater focus on technologies such as batteries and power plants using hydrogen made from excess renewables.

And there will be a greater need to manage demand, for example encouraging people to charge their cars or use appliances when there are high levels of renewables available.