What women want

From shattered glass ceilings to celebratory statues and belated police apologies, Helen Hubert considers the importance of female representation

I AM a feminist failure.

Ashamed as I am to say it, while I firmly believe in the social, economic, and political equality of the sexes and support the fight for women to have equal rights and opportunities in every sphere, I would make a woeful role-model for the cause.

For a start, despite resenting the way women are so often judged by their appearance, I enjoy wearing make-up and dresses – I even shave my legs (oh, the vanity!). I know next to nothing about cars and my parallel parking skills are an embarrassment (women drivers!). Although I work and earn my own money, I could not afford the mortgage on my house without the help of my husband (so dependent!). I’m far too exhausted to ‘have it all’ (so weak!) and I sometimes struggle with self-confidence (so meek!).

I hereby submit my sincere apologies to the sisterhood (whatever that is).

However, it is not lost on me that the mere fact I felt compelled to pen the above paragraph of blatant self-deprecation might be, at least partly, down to the societal pressures that have been placed on my gender for centuries – and still are.

Studies have shown that women who self-promote or behave assertively are judged as more pushy and arrogant than their male peers displaying the same behaviour. It’s not surprising, then, that they often put themselves down when voicing their opinions, to soften the force of their words, lest they be deemed conceited, smug, or preachy. All of which I am, obviously.

Of course, there is really no right or wrong way to be a feminist. Or a woman. Or a man. Or anything in between for that matter. We are all part of the perfectly imperfect diverse mess that is humanity and it is ridiculous to try to reduce us down to stereotypes.

Which is all an unnecessarily convoluted way of introducing the real topic of this article: female representation.

Several news stories in the past few weeks have got me pondering on this issue.

First was the good news.

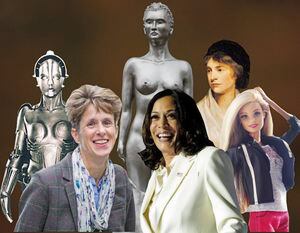

Four years after Hillary Clinton failed in her bid to become America’s first woman president, Kamala Harris is set to become the country’s first female vice-president. Not quite the top job but tantalisingly close to it.

Similarly, and much closer to home, Heidi Soulsby was appointed Guernsey’s first female deputy chief minister.

Why does that matter? After all, surely it is a person’s ability to do a job that is important, not their gender.

You only have to listen to the words of Kamala’s victory speech for the answer:

‘… while I may be the first woman in this office, I will not be the last, because every little girl watching tonight sees that this is a country of possibilities. And to the children of our country, regardless of your gender, our country has sent you a clear message: Dream with ambition, lead with conviction, and see yourselves in a way that others may not, simply because they’ve never seen it before, but know that we will applaud you every step of the way.’

In other words, the reason it matters is because young girls deserve to be able to grow up knowing that such roles are just as achievable (or unachievable) for them as for their male counterparts.

It’s not about women being better or worse than men.

It’s about representation.

Now the not so good news.

A new statue in honour of ‘mother of feminism’ Mary Wollstonecraft has just been unveiled in North London. The culmination of the ‘Mary in the Green’ project – conceived to help redress the fact that more than 90% of London’s statues commemorate men, leaving many worthy women uncelebrated and ignored – it took 10 years and more than £140k to come to fruition.

So, how was this seminal 18th century writer, philosopher and advocate of women’s rights immortalised?

Erm, on first impressions, with what appears to be a naked silver Barbie standing atop an amorphous mound which looks like something my kids might have sculpted out of Play-Doh.

I want to like it but... well, it makes the donkey statue at the Friquet look like an artistic masterpiece.

According to its creator, Maggi Hambling, the sculpture is intended to be ‘for’ Mary Wollstonecraft, not ‘of’ her. It represents the birth of a movement, an ‘everywoman’ emerging from a wave of combined female forms – and the figure had to be nude, says Hambling, because ‘clothes define people’.

Despite it forming only a small part of the total sculpture, many critics have focused, unsurprisingly, on the idealised everywoman pinnacle of the monument. How, they ask, can this figurine’s Barbie-like proportions and (gasp) prominent pubic hair possibly represent all women?

In fact, even Barbie is more representative of women in general these days, with manufacturer Mattel now selling dolls featuring a range of sizes, colours and even disabilities.

Perhaps a better comparison is with the maschinenmensch robot from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis – a terrifying mechanical temptress who winds up being burned at the stake. I don’t know for sure, but I suspect that’s probably not what the artist was aiming for either.

It is hard to imagine a man being memorialised in such a fashion, although I would be far from disappointed if Trump’s lasting legacy turned out to be a statue of him as a tiny evil-robot-Ken-doll (not nude though, please – the mere concept makes me feel nauseous).

Still, love it or hate it, it can’t be denied that Hambling’s sculpture has got people talking. It even prompted me to dust off my copy of A Vindication of the Rights of Women, which has languished untouched in my bookcase for more than a decade. So, in that sense, it has fulfilled its purpose as a provocative piece of public art and raised awareness about an important historical figure.

Still, I can’t help but feel that Mary Wollstonecraft deserves better.

Perhaps more troubling in terms of female representation was the news last Friday that West Yorkshire police had issued a belated apology to the victims of Peter Sutcliffe, otherwise known as the Yorkshire Ripper, following his death from Covid-19.

Sutcliffe was convicted of murdering 13 women in northern England between 1975 and 1980 and attempting to kill seven others.

Many of his victims were dismissed as prostitutes at the time and police were later found to have badly bungled the investigation. The force’s misogynistic and sexist attitudes even sparked marches and protests.

During the investigation, senior detective Jim Hobson said that the killer ‘has made it clear that he hates prostitutes. Many people do. We, as a police force, will continue to arrest prostitutes. But the Ripper is now killing innocent girls’.

During the trial, Sir Michael Havers, the prosecutor who was attorney general at the time, said: ‘Some were prostitutes but perhaps the saddest part of the case is that some were not. The last six attacks were on totally respectable women.’

It is easy to dismiss such attitudes as being of their time, a part of history we have left behind. Sadly, that’s not true – the past leaves a lasting imprint which echoes through the present, affecting our unconscious thoughts and contributing to our prejudices.

Distinguishing between ‘innocent’ or ‘respectable’ women and sex workers, or even just those considered promiscuous, was as wrong then as it is now. Sutcliffe’s victims were all people and, in death and in life, should not have been defined merely by what they did for a living, or how they behaved. They were also wives, mothers, friends, confidantes.

The impact of such an attitude on their loved ones, as well as on the survivors of Sutcliffe’s attacks, must have been devastating.

The police were right to apologise. Shame it was 40 years too late.

hhubert@guernseypress.com