So you want to be a States member?

What you feared is true. Deputies don’t know what they’re doing. But then, how can new ones? Richard Digard looks at the induction process available, whether it’s compulsory – and asks who attended the sessions

YOU might recall that when senior and highly-regarded civil servant Richard Evans retired the other day, he had this to say of some of those deputies he had helped steer through the quagmires of government: ‘The States we’ve got at the moment, in my view, is quite naive. A lot of well-meaning, dedicated, good people, but sometimes I wonder whether they have a grip on reality. I’m not sure all of them fully understand what being a politician is.’

It’s a good quote. But then Mr Evans – the public sector’s ‘Mr Fixer’ when there was a difficult job to be done – always had a knack of summing things up with a choice phrase or two. The question, however, is whether his assessment of Guernsey’s political class is correct or not.

In a word, yes. What you’ve long suspected is true. States members generally don’t know what they’re doing.

Before anyone gets too upset by that, it’s pretty self-evident, isn’t it? By definition, a candidate, if successful, will be a complete rookie on entering the States. Even those who have tried to bone up on the intricacies of government ahead of an election are staggered by how much there is to learn about a multi-billion pound organisation employing nearly 5,000 individuals.

Start a new job yourself and how much do you really know about the business, its culture, internal workings and existing projects?

That’s why the States has an extensive induction process for new deputies and a development programme for those already in post. I’m grateful to Frossard House’s communications people for a comprehensive response to what that entails and links to existing material. And there’s a lot of it.

Aware of the potential problems with what new members don’t know, the programme was rolled out after the 2020 election. It included a wide range of presentations/workshops put on by relevant staff to support States members’ understanding of issues they inevitably encounter: sessions on data protection, media, IT, governance, rules of procedure and finance. Refresher sessions were then put on for some topics in late 2021.

As you know, I’m critical that we don’t do enough to set out the complexities of the role of deputy, how onerous (and responsible) it is and the skills and experiences that would make someone an ideal candidate. In fairness, however, the system does try to ensure wannabes go into it with their eyes open.

An Information for Prospective Candidates leaflet is pretty clear on the three main ‘jobs’ of deputy – member of the States of Deliberation, member of States committees and ‘working with members of the community’, AKA constituency matters. It’s also blunt on the amount of work required:

In the States – ‘It is unlikely that a member could be properly informed on every matter before a busy States’ meeting without at least 20 hours’ preparation time; and for some the preparation time will be double that.’

On committees – ‘Excluding presidents of committees, membership of a committee could take up anything from around 10 hours to around 60 hours a month.’

In the community – ‘A deputy’s workload working directly with members of the Community may range from a few hours a month to ten or more hours a week.’

Former States member Allister Langlois has also produced a pretty exhaustive and useful guide for would-be politicians – ‘…a deputy cannot truly do an effective job if they do not regularly consult people in some way’ – sound advice you can’t help feel is largely ignored, especially now the parish link has been broken following island-wide elections.

Anyway, all this effort on preparation and training begs two questions: do new deputies have to attend the induction process and how effective is it? Especially relevant since nearly half the House (18 members) are newbies.

The official response: ‘Sessions were not mandatory, as it would be very difficult to do this, and given the number and range of induction sessions put on, it’s not possible to provide a breakdown of which members attended which sessions.’ So I can’t tell you who bothered to turn up or not.

However, the States Assembly & Constitution Committee (Sacc) has reviewed the effectiveness of the induction sessions and acknowledges it can be improved and extended for the 2025 election.

But only 19 deputies responded to the feedback survey, which doesn’t suggest massive participation in the process or engagement with trying to up-skill the role of deputy.

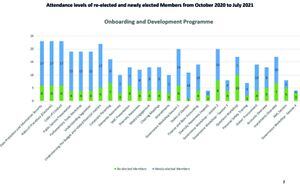

As Sacc noted, ‘…the success of sessions has often relied on member participation and feedback. On a number of occasions, members have accepted invitations to sessions and then subsequently failed to turn up…’

And according to Sacc’s statistics, attendance was patchy – was it the same individual who swerved the courses where all but one new deputies attended I wonder? – and our elected representatives reckon they’re pretty clued up on governance issues. Which is alarming.

So what can we make of this dip into the induction process? Firstly, it’s widely recognised here and elsewhere that the relevant knowledge and skills materially assist deputies in the performance of their parliamentary duties (the absence of same means they’re likely to do a bad job, we can assume). In addition, the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association says that legislatures, including Guernsey, should take measures to increase members’ knowledge and skills.

In short, having deputies who know what they’re doing is vital for good government. This is recognised by the States, which works hard on the professional development of elected members. It’s a voluntary process, however, with no transparency or reporting on who takes part or not. And, perhaps inevitably, electors have little, or only subjective, evidence of who develops into a good (skilled and knowledgeable) deputy.

My take on the process is twofold. One, help for deputies is extensive, in depth and improving. Taxpayers and electors should be reassured by that but clarity on who attends (as we get for attending meetings) would be helpful.

Two – the biggie in my view – it’s all retrospective. Which is why I’m reliably informed there’s one new deputy who thought all he had to do was turn up for States meetings.

As an aside, while researching this piece I came across the following in the States’ Review Committee’s second policy letter: ‘Constitutionally, all members of a committee are equal but it is widely recognised that the quality of a president can make or break a committee.’

If you have any thoughts on that do please let me know – rdigard@guernseypress.com