Five things to know about Germany’s surging nationalist party

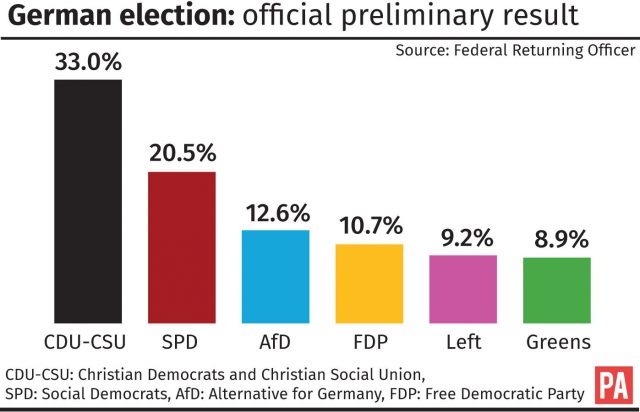

Alternative for Germany won 12.6 of the vote in Sunday’s German election to become the third largest party in the Bundestag.

Alternative for Germany (AfD) was founded four years ago at the height of the eurozone crisis, when opposition to a German bailout of other countries using the common currency was strong.

The party narrowly failed to pass the 5% threshold to enter parliament in 2013 on a Eurosceptic platform, a hurdle it took handily this time following a campaign focused heavily on chancellor Angela Merkel’s refugee policy.

The party received 12.6% of votes in Sunday’s election to become the third-largest caucus in Parliament behind Ms Merkel’s bloc and the Social Democrats.

Political analysts say AfD’s success is all the more remarkable because it has drifted steadily rightward in a country where voters are sensitive to any revival of the extreme nationalism that brought Adolf Hitler to power 84 years ago.

Strong in the east

Alternative for Germany’s base is in the formerly communist east of the country. Anxiety over immigration is particularly strong in the east, despite the relatively low percentage of immigrants in the region, and leaders there have been among the most hard-line in their views.

AfD’s leader in Thuringia state, Bernd Hoecke, called for a “U-turn” in the way Germany remembers its Nazi past. In neighbouring Saxony, a prominent member of the party, Jens Maier, declared that Germany’s “culture of guilt” over the Second World War should be considered over.

Leadership in-fighting

AfD’s first leader, Bernd Lucke, left the party two years ago after losing a leadership battle against Frauke Petry.

Ms Petry has since become embroiled in a spat with other senior figures after urging her party to exclude members who express extremist views with the aim of attracting moderate voters.

She stormed out of the party’s press conference a day after the election and insisted she would not join AfD’s parliamentary caucus.

How far right?

AfD’s opponents have described the party as a far-right or even extreme-right movement, citing the xenophobic views expressed by some of its members.

Political scientists caution that while there are extremists in the party’s ranks, its ideas are closer to those once held by the conservative wing of Ms Merkel’s party than to the far-right fringe of German politics.

Still, some in AfD have expressed revisionist views of German history with anti-Semitic ideas without being kicked out of the party, and it is the farthest right party to win seats in parliament in about 60 years.

Party co-leader Alexander Gauland prompted controversy again weeks before the election by saying that “we have the right to be proud of the achievements of Germans soldiers in two world wars”.

Cash injection

All German parties receive public funding based on the number of the votes they receive in elections.

AfD has already collected millions of euros from entering 13 state assemblies and the European Parliament over the past four years.

The party can expect a further windfall from Sunday’s federal election that will allow it to build a formidable operation in Berlin with hundreds of full-time staff.

Russia-friendly

Alternative for Germany has taken a very pro-Russia stance, calling for Western sanctions against Moscow over its involvement in the Ukraine conflict to be dropped.

Ms Petry travelled to Russia earlier this year for a secretive meeting with members of Russian president Vladimir Putin’s party and AfD has courted Russian-speaking German voters with considerable success.

During the final weeks of the campaign, AfD was heavily promoted by Russian-language social media accounts.