South Korean and Japanese leaders meet again to improve ties

Japanese premier Fumio Kishida is making a two-day visit to Seoul, reciprocating a mid-March trip to Tokyo by South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol.

The leaders of South Korea and Japan met for their second summit in less than two months on Sunday as they push to mend long-running historical grievances and boost ties in the face of North Korea’s nuclear programme and other regional challenges.

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida arrived in South Korea for a two-day visit, which reciprocates a mid-March trip to Tokyo by South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol. It was the first exchange of visits between the leaders of the Asian neighbours in 12 years.

South Korean media attention is focused on whether Mr Kishida will make a more direct apology over Japan’s 1910-45 colonial rule of the Korean Peninsula

Such comments could help Mr Yoon win greater support for his push to build stronger ties with Japan and ease domestic criticism that he has pre-emptively made concessions to Tokyo without receiving corresponding steps in return.

Ahead of the summit, Mr Kishida and his wife, Yuko Kishida, visited the national cemetery in Seoul, where they burned incense and paid a silent tribute at a memorial.

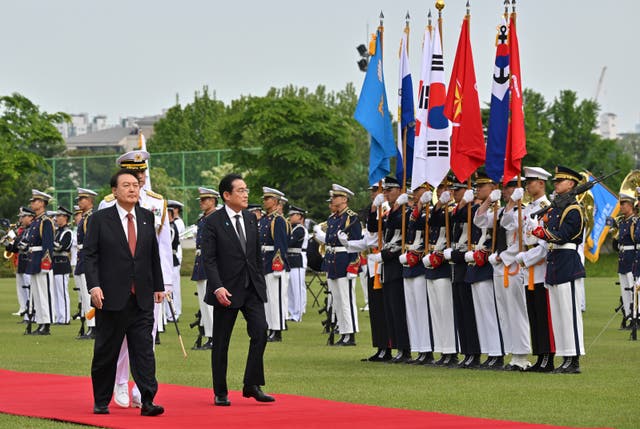

He later reviewed a South Korean guard of honour with MR Yoon at an official welcoming ceremony at the South Korean presidential office.

“I hope to have an open-hearted exchange of views with President Yoon based on our relationship of trust,” Kishida told reporters before his departure to Seoul. “Since March, there have been various levels of communication in areas including finance and defense, and I plan to further develop this ongoing trend.”

Sunday’s summit was to focus on North Korea’s nuclear programme, South Korean-Japanese economic security and overall relations, and other unspecified international issues, according to South Korean and Japanese officials.

In recent weeks, the two countries have also withdrawn the economic retaliatory steps they had earlier taken against each other in previous years when their history row rekindled.

The most recent sticking point in ties between Seoul and Tokyo was 2018 court rulings in South Korea that ordered two Japanese companies to financially compensate some of their ageing former Korean employees for colonial-era forced labour.

The verdicts angered Japan, which has argued that all compensation issues were already settled when the two countries normalised ties in 1965.

The strained South Korea-Japan ties complicated US efforts to build a stronger regional alliance to better cope with rising Chinese influence and North Korean nuclear threats.

In March, however, Mr Yoon’s conservative government took a major step towards mending the ties by announcing it would use local funds to compensate the forced labour victims without demanding contributions from Japanese companies. Later in March, Mr Yoon travelled to Tokyo to meet Mr Kishida.

Mr Yoon’s push drew a strong backlash from some of the forced labour victims and his liberal rivals at home, who have demanded direct compensation from the Japanese companies.

Mr Yoon has defended his decision, saying greater co-operation with Japan is required to tackle a set of challenges such as North Korea’s advancing nuclear programme, the intensifying US-China strategic rivalry and global supply chain problems.

During a joint news conference, Mr Biden thanked Mr Yoon “for your political courage and personal commitment to diplomacy with Japan”.

Victor Cha, senior vice president for Asia and Korea chairman at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, wrote in an analysis published last week: “White House officials have expressed some frustration with the tepid response from Tokyo on the forced labour compensation deal and hope that Kishida will use an upcoming visit to South Korea in early May to do more.”

Mr Yoon, Mr Biden and Mr Kishida are expected to hold a trilateral meeting later this month on the sidelines of the Group of Seven meetings in Hiroshima to discuss North Korea, China’s assertiveness and Russia’s war on Ukraine. Mr Yoon was invited as one of eight outreach nations.

After his March summit with Mr Yoon, Mr Kishida said he upholds the positions of previous Japanese governments including one carried in the landmark 1998 joint declaration by Tokyo and Seoul on improving ties, but did not make a new apology.

In the 1998 declaration, then-Japanese prime minister Keizo Obuchi said “I feel acute remorse and offer an apology from my heart” over the colonial rule.

Asked whether he will discuss the forced labour victims with Mr Yoon, Mr Kishida said in his pre-departure comments: “We will frankly exchange our views on this.”

Seoul and Tokyo have a slew of other sensitive historical and territorial disputes, mostly related to the Japanese colonisation.

In a reminder of the delicate nature of their ties, diplomats between the two countries last week were involved in a spat over a South Korean politician’s visit to disputed islets located in the waters between the two countries.

Earlier, Seoul protested when Mr Kishida made religious offerings at a Tokyo shrine which it views as a symbol of Japan’s wartime aggression.