PFA’s Jeff Whitley urges players to use phones to ask for help, not place bets

The midfielder-turned-counsellor now helps players deal with the type of mental-health issues that wrecked his own promising career.

Online gambling is the biggest cause of mental health-related issues for young footballers, former Manchester City and Northern Ireland star Jeff Whitley has told Press Association Sport.

Now a member of the welfare team at the Professional Footballers’ Association, Whitley has witnessed a huge increase in the number of current and former players asking for help with addictions, anxiety and depression.

“If you look at the past, there were a lot of people with gambling and drink problems but times have changed and we’ve got new challenges,” said Whitley.

“There’s also gaming and we see young lads having problems with that. It can be a nice pastime but unfortunately some lads aren’t setting sensible boundaries. They are going back to their digs after training and playing from two in the afternoon to two in the morning and then not being right to train and it having an impact on their mental health.

“But gambling is the biggest problem for a number of reasons. It’s different to alcohol or drugs, which you can see or smell when players come into the club. The same with a sex addiction, they would look like they’ve been up all night.

“With gambling, people can put a mask on. It can be months before anyone would know they’re really struggling.”

Whitley explained there are multiple “triggers” for players in terms of developing a problem, from being pressured into joining the card school on the back of the bus with established first-team players to the “constant bombardment” of betting adverts when watching live sport on television.

Looking back on his career, which saw him make City’s first team at 17 and play for Northern Ireland at 18 only to spiral out of control thanks to injuries and his self-destructive behaviour, Whitley knows the importance of surrounding yourself with the right people, taking as much care of your mind as you do of your body and asking for help when you need it.

“The drinking culture was accepted. I remember people saying ‘you’ve got to get out of it’ but nobody ever told me there was a solution,” he said.

“But it’s hard to stop something when nobody gives you a solution. So my drinking just progressed and progressed.”

Eventually, City had enough and he was released in 2003. Second, third and fourth chances at Sunderland, Cardiff and Stoke were spurned as the drinking got worse, cocaine was added to the mix and “the drama” increased.

Some of this was caused by football’s habit of shunning injured players as though they are infected with bad luck, some was a consequence of “knocking about with the wrong people” but part of it was also down to Whitley never dealing with the psychological impact of his parents dying when he was 11.

“I had several incidents where other people would just stop, like getting done for drink-driving. Who parties on their own in their car? That’s not normal,” he said.

“I’d changed cities, changed jobs, changed friends, changed my drinks, lagers to shots, changed girlfriends but it didn’t matter until I got to the point where I said I’m done. If I carry on like this I’m going to die.”

That is when Whitley did the “hardest but best thing” he has ever done – he called Sporting Chance, the clinic Tony Adams set up after his own problems with alcoholism.

“My kids have never seen me drink. My wife has seen my worst moments, she needs a medal.”

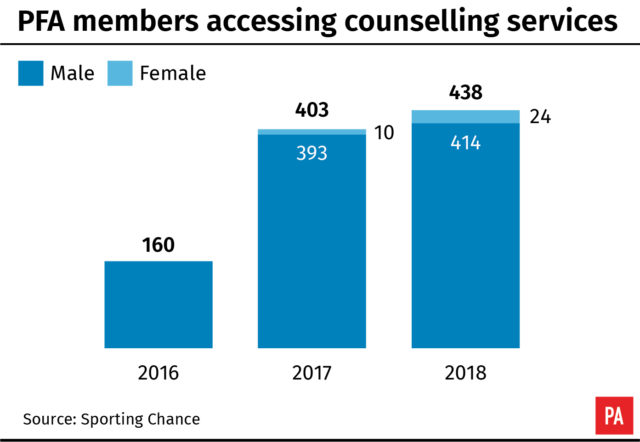

For him, the almost three-fold increase in the number of players accessing the PFA’s counselling network over the last two years is a positive, not a negative, as fewer people are suffering in silence and more people are getting the help they need.

“It doesn’t have to be a massive drama or rock-bottom moment for them to pick up the phone,” he said.

“If they’re struggling with something on a regular basis, pick up the phone or send a message and we’ll look at the best way of supporting you.”